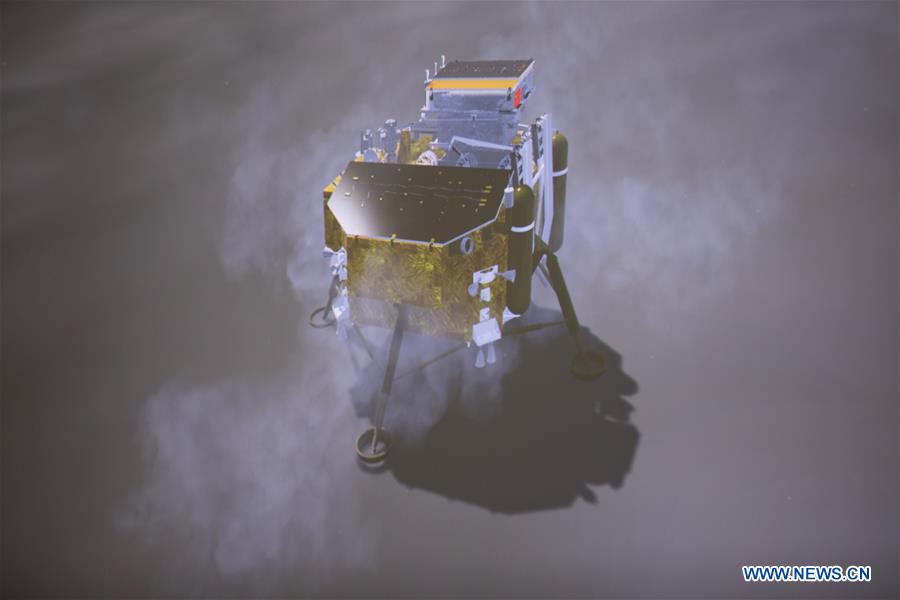

A simulated landing process of Chang'e-4 lunar probe is seen through the monitor at Beijing Aerospace Control Center in Beijing, capital of China, Jan. 3, 2019. China's Chang'e-4 probe touched down on the far side of the moon Thursday, becoming the first spacecraft soft-landing on the moon's uncharted side never visible from Earth. The probe, comprising a lander and a rover, landed at the preselected landing area on the far side of the moon at 10:26 a.m. Beijing Time (0226 GMT), the China National Space Administration announced. (Xinhua/Jin Liwang)

By Xinhua writers Quan Xiaoshu, Yu Fei

BEIJING, Jan. 3 (Xinhua) -- China's Chang'e-4 lunar probe has made the first-ever soft landing on the far side of the moon. Experts believe that the precise landing will help prepare the country for its following lunar exploration and future expeditions to other planets.

The probe, comprising a lander and a rover, landed at the preselected landing area at 177.6 degrees east longitude and 45.5 degrees south latitude on the far side of the moon at 10:26 a.m. Beijing Time, the China National Space Administration announced.

The landing area is the Von Karman Crater, named after a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer and physicist, within the Aitken Basin. The area was intentionally selected after much consideration.

"When discussing the Chang'e-4 mission, we thought we should attach more creativity and functions to it, enabling it to do more challenging things," said Wu Weiren, chief designer of China's lunar probe program.

The far side of the moon was not the only first at first. Some experts even considered landing on other celestial bodies, but it would have required great changes made for the probe.

As Chang'e-4 began as a backup for Chang'e-3, many of their components and parts were designed and manufactured together, which allowed little room for changes, according to Sun Zezhou, chief designer of the Chang'e-4 probe, from China Academy of Space Technology.

Since the moon's revolution cycle is the same as its rotation cycle, the same side always faces the earth. The other face, most of which cannot be seen from Earth, is called the far side or dark side because most of it is uncharted.

"The rugged terrain of the moon's far side has made the landing much more risky than on its near side. However, more accurate landing technology is needed in the future," Sun said.

"For example, if we want to send detectors to the moon's bumpy polar regions and descend them on a relatively small area with permanent sunshine, it will demand very high landing precision," he explained.

"If we want to build a scientific research station on the moon, we will need to land multiple probes within the same area so that they can be assembled easily into a complex, which requires even greater landing accuracy," he said.

"So solving the challenges of the Chang'e-4 mission can lay the foundation for the following lunar exploration and future landing on other planets," he noted. "We hope that we will have the capacity to get to the whole moon and even the whole solar system in the future to support our deep space scientific explorations."

After the far side of the moon is determined as the destination, the specific landing area is narrowed by various restrictions.

Chang'e-3, launched in 2013, is the first Chinese spacecraft to soft-land on and explore an extraterrestrial object. Its thermal control system and solar wings are designed in line with the sunshine conditions at its landing area, Sinus Iridum or the Bay of Rainbows, at around 45 degrees north latitude. With almost the same design, Chang'e-4 is therefore preferred to land on an area between 40 and 50 degrees in latitude, Sun said.

After deciding the latitude, experts went on to consider the longitude. "To set up the communication link between the earth and the moon's far side, the relay satellite 'Queqiao' was launched in May and is now running on a halo orbit around the second Lagrangian point of the earth-moon system. It could only cover an area between dozens of degrees in longitude away from the central point of the far side for all-time communications," Sun said.

"And we don't want the elevation angle too small in case signals are hindered by surrounding mountains when the probe communicates with the relay satellite," he added.

Within the circled latitude and longitude, scientists pinned their eyes on the Aitken Basin, the largest, deepest and oldest crater in the solar system. It may contain the earliest information about the moon, for example whether it once had water. Exploration in this area will provide firsthand data and clues for the evolution of the moon, earth and solar system.

About 2,500 kilometers in diameter and 13 kilometers in depth, the Aitken Basin has a small crater, Von Karman, inside it. The latter, 180 kilometers in diameter, is relatively flat in its bottom, making it the best choice for landing.

About 13 degrees in longitude away from Von Karman, there is Chretien Crater, a perfect alternative landing area. If Chang'e-4 fails to touch the surface of Von Karman on the first day, it could land on the alternative area on the second day.

Shen Zhenrong, a designer of the Chang'e-4 probe, believes the mission will be a contribution for the whole world. "Although we don't know what Chang'e-4 will discover yet, the exploration is highly possible to influence generations of people."